“We had stayed up all night, my friends and I, under hanging mosque lamps with domes of filigreed brass, domes starred like our spirits, shining like them with the prisoned radiance of electric hearts. For hours we had trampled our atavistic ennui into rich oriental rugs.”

These are the first sentences of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s “Founding and Manifesto of Futurism.” Soon the idyll is disturbed by the “famished roar of automobiles” and the group decides to leave the mosque chasing “after Death” like “young lions” (Marinetti 1909: 49-50). The juxtaposition of an orientalist idyll, a modern techno-world, and death is intriguing and reminiscent of the aesthetic universe most recently produced by the propaganda of the Islamic State (ISIS).

Futurism glorified cars and modern cities, and emphasized speed, technology, youth, and science. On the other hand, Futurism incorporated strong anti-female notions though “contemporary civilization” had begun to transcend them. Futurists were opposed to parliamentary democracy and sympathized with nationalism and colonialism. A similarly curious combination of modernism and conservative values is constituted by the “soft culture” of ISIS jihadism. The most obvious modern characteristic of this new image of fundamentalism is the highly aestheticized recruiting material distributed by ISIS via the internet.

Summary

The "Futurist" Aesthetics of ISIS

I show by means of empirical analyses and theoretical reflections that the aesthetics of the Islamic State is “futurist.” Italian Futurism praised violence as a means of leaving behind imitations of the past in order to project itself most efficiently into the future. Futurism glorified cars and modern cities, and emphasized speed, technology, and youth.

ISIS overcomes the postmodern, pessimistic futurism of “cyberpunk” and links itself to the optimistic attitude that was common in Italian Futurism in the early twentieth century. ISIS returns to modernism. Cyberpunk stands for the exhaustion of the industrial economy while Italian Futurism is the origin of an optimistic kind of Science Fiction.

In ISIS wars, real, breathing bodies are steering real, steaming machines. In a “futurist” way, ISIS rediscovers the “real machine” as opposed to the postmodern, virtual “nano” machine. ISIS also brings back a corpo-reality into a world that has become more and more mediated by technology. Leaving the “postmodern” behind, ISIS goes back to the future imagined by Futurism.

Fig. 2: Tullio Crali: "Incuneandosi nell'abitato (in tuffo sulla citta" [Nosedive on the City] (1939)

Fig. 3 Opening Scence from "The Clanging of the Swords" Part 4

Islamic Futurism?

The Islamic State does not only excel through the extensive use of high-tech weapons, social media, commercial bot, and automated text systems; by putting forward the presence of speeding cars and tanks, mobile phones, and computers, ISIS presents jihad life as connected to modern urban culture. I show that the aesthetics of the Islamic State is “Futurist” by comparing it with Italian Futurism. Futurism praised violence as a means of leaving behind imitations of the past in order to project itself most efficiently into the future. A profound sense of crisis produces in both Futurism and jihadism an apparently nihilistic attitude toward the present state of society that will be overcome through an exaltation of technology.

Fig. 7: Explosion of light in "Let's go for Jihad" reminiscent of Futurist "lines of force"

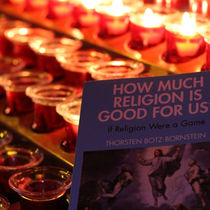

“Joyfully tearing down the compartment walls that conventionally separate fascist studies from research into jihadism and gleefully crossing the boundaries between aesthetics and politics, Thorsten Botz-Bornstein challenges—or, rather, provokes—the reader to reconfigure the space that fascist and terrorist destructiveness occupy in the contemporary media, party-political, and historical imaginations. Not afraid to alienate experts in both fields of study, Botz-Bornstein creates new connections and suggests fresh juxtapositions with futurist abandon. Though the ludic may prevail over the academic, The Political Aesthetics of ISIS and Italian Futurism exposes the veins of a perversely politicized brand of modernism that throb just under the surface of two ideologies claiming to be rooted in an imperial or religious tradition as well as expresses itself in deliberately staged acts of spectacularly aestheticized destruction.” Roger Griffin, Oxford Brookes University, author of Fascism, Totalitarianism and Political Religion.

ISIS and Cyberpunk

The principal objective of the present book is to show that ISIS – and with it a large and relatively complex tradition of radical Islam – intends to return to Futurism and modernism. The situation that is going to be overcome can be called “postmodern” but also cyberpunk. Cyberpunk became a catchword or a symbol for a certain attitude current in postindustrial Western and Japanese culture in the 1980s. Cyberpunk stands for the exhaustion of the industrial economy and the exhaustion of the avant-garde. Futurism, on the other hand, is the origin of an optimistic kind of Science Fiction, and for the largest part of the twentieth century Science Fiction maintained this optimistic attitude towards the future.

ISIS returns to Futurism by overcoming both postmodernism and cyberpunk. One fact that supports this thesis is that ISIS evokes in its media an aesthetic techno-universe full of machines and urbanity. The futurist machine is not the virtual, postmodern bio-digital machine inserted into bodies; it is rather the mechanical, edgy, and noisy machine that is also preferred by ISIS. ISIS has rediscovered the “real machine” and as a consequence it has also rediscovered the reality of the body. In ISIS wars, real, breathing bodies are steering real, steaming machines. ISIS brings back a corpo-reality into a world that has become more and more mediated by technology. ISIS also shows that revolutions are not limited to digital revolutions silently undermining digital systems but that revolutions can be real.

Left: Tato, Aeroplani e Metropoli (1930)

The Twin Towers attack is a symbolic message announcing the end of Cyberpunk and inaugurating a new interpretation of the future determined by “Islamic Futurism.” In Italian Futurism, from the 1930s onward, airplanes and aviation became the most important incarnations of a particular aesthetics.

Tullio Crali: Bombardamento urbano, (1935)

ISIS also rediscovers space. At a time when every millimeter of earthly space has been conquered and colonized up to the point that we have to go into outer space or into cyberspace in order to experience adventures, ISIS confronts us with a geographical space that is not merely mental but real because it can be perceived by our five senses. Inch by inch of this space is conquered by real, breathing bodies who are driving real machines. All this is futurist and not cyberpunk.

Unlike André Glucksmann, who puts a genuine Cyberpunk image on the front cover of his book on the "nihilism" of 9/11 terrorists (a picture of the destroyed ground zero), I believe that Bin Lahden's message was futurist.

U. Boccioni:'s Elasticity (1912) shows an explosion.

Futurist optimism is violent, fast, and concrete, and wants to overcome nature through technology. Cyberpunk is pessimistic and passive. In Cyberpunk, nature gets slowly overgrown by an abstract technology that has almost become organic.

A Study in Political Aesthetics

I examine the aesthetics of this material via Futurist devices. Both Futurism and Daesh “decompose” objects over time and space. Daesh videos manifest a great interest in movement, and its cinematic manipulation follows elaborate devices making dynamic movement plausible. Fast forward and fast backward movements of the same scenes create visual effects able to make movement more palpable. Images of exploding cars with bodies flying through the air are often repeated in slow motion. This is similar to Futurist manipulations of speed, which often seek to show the same objet several times at different places, just as if our eye is too slow to grasp the “real” speed of the event. In Futurist photography, this was obtained through complicated superimpositions (the “photodynamism” developed by the photographer Anton Giulio Bragaglia).

When violence is ritualized and aestheticized to such an extent, the self-image of the daesh fighter is not that of the soldier-pawn, but of the “cool,” narcissistic warrior. This is precisely the image that also Futurists adopted. Jihadism and Futurism share a nihilistic attitude toward the present state of society and tradition that springs from a profound sense of crisis. Apocalypse is envisioned as the prelude to a utopian future. A certain aesthetics, deliberately provocative and incendiary proclamations, as well as the embrace of mass media channels and certain political ideologies and affiliations are common to both.

Elio Luxardo: Futurist Portrait of Marinetti

Giacomo Balla: La modernité futuriste

The ISIS phenomenon is a prime example of the “aesthetization of politics.” In videos even the cruelest scenes are sprinkled with poetry. This propaganda is an aestheticized celebration of violence. Also, Futurist poets and painters were supposed to be “beautiful in their violence” (Francesco Pratella in his “Manifesto of the Futurist Musician”) and W. Benjamin saw Futurism as a manifestation of the aesthetization of violence.

The research is supposed to help handling the concept of “progressive conservatism” more correctly. It will make clear the necessity to distinguish moral values and religious contents from the attitude with which those values are defended. A progressive spirit does not make Islamic fundamentalism or Italian Futurism more modern irrespective of its content. To be progressive can refer merely to the application of abstract structures while “modern” should refer to concrete values. It is easy to fall into the trap of identifying the progressive with the modern.

Luigi Russolo, The Revolt, 1911

"La macchina sta al centro del mondo immaginario futurista. Si tratta della macchina esterna, farraginosa e ingombrante da non confondere con la machina internalizzata et recombinante dell’epocha bio-informatica, l’epoca nostra, l’epoca nuova che inizia dopo la fine del secolo che credeva nel futuro, e si mostra in tutta la sua potenza immaginaria e pratica con la realizzatione del Progetto Genoma." Franco Berardi, Dopo il Futuro

"Over a course of a hundred years, the twentieth century has moved from Futurism to Cyberpunk. Almost in parallel develops a new and immensely intriguing cultural phenomenon: Islamic fundamentalism. Can those two developments be linked?"

Contents

Introduction

1. Comparing the Incomparable

2. Art and Non-Art

3. Islamic Futurism

4. Methodology

4.1. Why Aesthetics?

4.2. Approaching Futurism

4.2.1. Futurism and “Marinettism”

4.3. Comparative Philosophical Studies and Historical Reality

4.4. Working on Futurism and Fascism

5. Two Social Movements

Chapter 1: Primitives of a New Sensibility. Comparing ISIS and Italian Futurism

1. Futurism or “No Future”?

2. Overcoming the Crisis

3. Four Main Themes

3.1. The Aesthetization of Violence and the Philosophy of Action

3.2. Modern or Non-Modern, Left or Right?

3.3. Technology, Modernity, and Lifestyle

3.4. Religion and the Sacralization of Politics

4. ISIS, Futurism, and Cyberpunk

Chapter 2: From Cyberpunk to Futurism: The Trajectory of ISIS

1. ISIS

2. Cyberpunk

3. Neo-Futurism

4. Futurism, Modernity, and Postmodernity

5. The Twin Towers through Futurism

5.1. The “Nihilist West”

5.2. Further Similarities and Differences between Cyberpunk and Futurism

Chapter 3: Terrorism and Cyberpunk

1. Terrorist Idealism

2. The Atomization of Society

3. The “Derealization” Effect in Modern Wars

3.1. Muslim Punk or Cyberpunk?

3.2. Dogmatism or Irony?

4. The Real Machine vs. the Virtual Machine

4.1. Futurist Bodies

4.2. The Futurist Machine of ISIS

5. The Reinvention of Space

6. Futurist Time

Chapter 4: Fascism, ISIS, and Futurism

1. What is Fascism?

2. ISIS and Fascism

3. Islamofascism

4. Modern or Anti-Modern?

4.1. Left or Right?

4.2. Another Type of Modernity

4.2.1. Mythology

4.2.2. Individualism

4.2.3. Religion

4.3. Relativism

5. Futurism

5.1. Futurism and Fascism

5.2. The Modernity of Futurism

Chapter 5: Islam

1. Progressive Conservatism

1.1. Modern Islam

2. Progressive is not Modern

3. Reformed Islam: Modern or Simply Progressive?

3.1. Modern Attitudes vs. Modern Values

3.2. The Progressive Anti-Modernism of ISIS

4. Progressive, Modern, and “Modernish”

4.1. Progressive vs. Moderate

5. From Islamism to ISIS: Which Kind of Modernity?

5.1. Modern or Postmodern?

Chapter 6: The Futurist Aesthetics of ISIS

-

“Caliphate Cinema”

1.1. Modern Media

1.2. Technology and Urbanism

1.3. From Al-Qaeda to ISIS or from Symbolism to Futurism

3. The “Futurist” Aesthetics of ISIS

4. The Aesthetization of Violence

Chapter 7: Artificial Optimism

1. Anarchism

2. Mass Appeal and the Shocking of the Masses

3. Puritanism

4. The Paradox of Nihilism

5. A “Modern” Subculture

Conclusion

Riot in the Galleria (1909), an early image by Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni, The City Rises (La città che sale) (1910), Cover picture.

Mario Sironi, "Paesaggio urbano," 1922

See this satirical article in HYPERALLERGIC