Kuwait: Japanophilia and Beyond.

How far does International Culture Penetrate?

The relevance of this research came to my mind the day a female student, fully covered with niqab leaving only a tiny slit for the eyes, came to my office to tell me about her enthusiasm for manga. I found that her manga club drawings testified some real artistic talent. Do you want to see my IMVU avatar, she asked? Out of her folder she took the drawing of a busty, scantily clad woman with tattoos and wallowing blond hair striking a rather provocative pose. “This is me,” she said.

Japanese culture is present in Kuwait in many different shapes. Universities have manga clubs, Japanese conventions like Q8con or PlamoQ8 draw thousands of people, cosplay competitions take place several times per year, and the Japanese and Korean embassies organize cultural events for young people. Universities invite specialists of Japan for well-attended talks. Of course, it would be wrong, naïve and – paradoxically – orientalist to find this surprising. All over the world young people are attracted by Japanese popular culture, so why should young Kuwaitis be different? Kuwait is a “normal” country in terms of internet access and communication, and the by far largest part of Japanese culture is not concerned by censorship. Haruki Murakami’s novels (though erotic in content) can be found in the main bookshop. A certain religious input in manga – as some characters can be derived from Shintoist deities – could raise concern, but even manga addicts seem rarely to be aware of the connections that mangas entertain with this quasi-animist religion. In this sense, “Japanophilia in Kuwait” is a non-topic except for people who mistakenly assume that Kuwait is an isolated culture steeped in the Wahhabist tradition banning everything that does not directly reflect religious truths.

The more interesting part of this research will thus concern the “beyond” that is contained in the title. Roughly speaking, there are two kinds of Japanophilia in Kuwait. Most young Japanophiles consume Japanese culture in the same way in which they consume Hollywood, soap operas or commercial Pop-music: without any ambition to unearth a cultural background linked to this entertainment, without using the newly discovered culture as a basis from which to view their own culture, and without using the new culture to construct for themselves a more nuanced Kuwaiti identity. However, a minority of young Kuwaitis is doing exactly this. I decided to search for this minority that seems to be constantly growing. It is not the “officially” modernized youth consuming mainstream Western culture and who has recently added Japanese and Korean mass culture to their menu of entertainment. Nor is it the – often affluent – youth that has in past decades acquired Western knowledge by spending time in the West and by attending Western universities. The youths I am talking about are not westernized in a straightforward, “modern” way but in a more tortuous, “funky,” individualized, or postmodern way. A more personal, reflective, and selective use not only of Japanese, but also of Western cultural elements makes those friends of Japan different from other consumers of popular culture.

As the example of the niqab girl with the sexy avatar shows almost literally, certain aspects of globalization in non-Western countries are not manifest but hidden. While in the past, “Westernized” Kuwaitis went most typically to a Western country to study, today young people can get “globalized” on their own, mainly through the internet. Most will approach American and/or Japanese mass culture. However, because of the individual way in which the internet functions as a medium, many people will mix their own cocktail of globalization and develop a subculture that is opposed to consumer culture. Contrary to mass culture oriented Westernized (or “Easternized,” since we are talking about Japan) culture, this subculture is also critical of more traditional Kuwaiti culture. Globalization through the internet functions in a very personal way since subjects can receive new ideas from foreign online friends. This kind of online communication is particularly frequent for people who are interested in Japanese or Korean culture.

The internet is one reason for the emergence of the “funky” type of globalized youngsters. Another reason is that in Kuwait or in the Gulf in general, Western subculture has a peculiar status. While in the realm of mass culture an equally strong pull from the Arab and the Western side does exist, in the realm of subculture, the Arab pull is relatively weak.

Subculture is usually defined as a possibly subversive cultural manifestation existing within a mainstream culture that opposes the latter’s “passively accepted commercially provided styles and meanings” (Riesman 1950: 361). This is why, in the Gulf, Western subculture elements tend to be absorbed very quickly by people who are looking for alternative cultural identities outside the realm of mass culture. There is a lot of regional popular Arab culture, but it is limited to pop music and traditional music. Who would be the Arab Jimi Hendrix? There is little Arab Indie music. This is unusual if one compares this, for example, with Japan. Japan has its own rock, punk, and hip hop scene to the point that some young Japanese do not need to revert to Western subculture at all but stay in the realm of their Japanese subculture.

The Gulf countries have nothing similar, and even the rest of the Arab world is in this respect arguably less well equipped than the West. Whenever the Arab world does not offer alternatives, Western elements tend to catch on very quickly in the Gulf. Kuwait has the most Twitter users per capita and Saudi Arabia has the most youtube users per capita (see Mocanu et al. 2013).

On the one hand, Kuwaiti popular culture has a relatively weak pull, but on the other hand, it is very exclusive. Imperatives about what should be done, how one should behave, and what should be consumed are very strong. This means that the person who listens to rap can easily be excluded from the group of more traditional Kuwaitis and will perhaps be labeled “American.” Again this is different from what happens in many other countries (Japan would again be a typical counter example). The constellation of “weak Arab subculture pull” plus Kuwaiti exclusiveness fosters the emergence of a subculture in which people look different, speak a different language, and can at times even be recognized by their body language. Usually their look is casual as they are wearing flip flops and shorts. Boys often have long hair, which is still frowned upon in traditional Kuwaiti circles.

The fact of speaking English often better than Arabic reinforces the above pattern. Though English education is not necessary for acquiring this subculture identity, its pervasiveness remains important. One reason why this type of counter culture develops relatively well in Kuwait is the strong presence of international schools. Since the pull of Arab subculture is weak anyway, people who have a partially “English” identity are more likely to be drawn to Western subculture. The spread of English education is unique in Kuwait, first because the population is affluent enough to pay for international schools; second because Arab public schools have a bad reputation. The colonial history might also play a (though minor) role here. However, this does not mean that all subculturally minded youths that I attempted to sketch above speak English very well.

The Meme Café

The “Meme Café” is a Japanese restaurant serving Japanese food and is located on the top floor of a videogame shopping mall in a slightly “messy” urban area of Kuwait city called Rihab (Hawalli Governorate). Here one can meet many of the above described young people. The customers are practically all male and, according to the waiter, practically all of them are Kuwaiti. The public here is not the rich crowd of Kuwaitis arriving with Ferraris and wearing Rolex. Those people can also be seen at shisha places in the city center or in Salmiya; nor is this the poorer Bedouin type who will often be seen in fast food outlets. In this mall we find a middle class youth that has had some access to education and educated themselves further over the internet. The mall’s rundown appearance (the lower floors are devoted to gaudy furniture adapted for the taste of poorer expats) draws a strict line between this subculture and the fancy world of Kuwait’s oil driven luxury lifestyle.

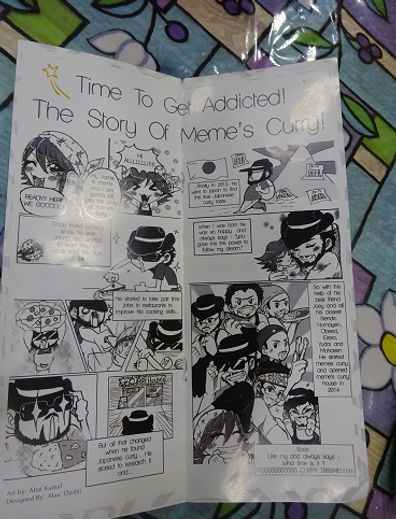

In the entire videogame part of the mall, "Japan" is important. Most businesses located close to the restaurant incorporate Japanese themes or are exclusively catering to Japanophile tastes. Shops with names like “Anime Planet” sell games and action figures. The Meme Café is extremely popular. While the five cheap Arab and Indian restaurants in the mall are almost empty, the Meme Café is always full and its premises have recently been extended. People eat Japanese curry, tempura and udon. The waiters are wearing head bands like Japanese waiters and the menu contains a manga telling the story of the Meme Café. Manga drawings by customers are hanging on the walls. But there are no chopsticks and the “meme special” versions of some dishes can be considered rather unfortunate interpretations of authentic Japanese food: a grid of mayonnaise stripes usually found on California rolls is put on the udon and on the curry. The restaurant’s website is entirely in Arabic though the printed menu also has English translations.

This is the crowd that I consider as representative of a new subculture in Kuwait and which I wanted to interview. How could I reach them? A survey addressing Japanophilia in Kuwait was a good starting point, though the more interesting (in terms of individuality, creativity, and critical consciousness) Japanophiles needed to be separated from the passive consumers. Therefore I decided, as I began interviewing people about their cultural interest, to introduce certain questions about Western subculture into the survey. The more individualist people are not only interested in Japan but also tend to search Western popular culture for particular themes. A Kuwaiti Japanophile who knows Jimi Hendrix and Louis Armstrong is most probably not the kind of consumer of manga consumer merely interested in fighting scenes. This is why I introduced a general knowledge question inquiring if they know some non-mainstream Western cultural items like Pink Floyd, 9gag or Clockwork Orange.

(...)

The whole article can be found as: ‘Kuwait: Japanophilia and Beyond: How far does International Culture Penetrate?' In S. Holland and K. Spracklen (eds.), Alternativity and Marginalisation: Essays on Subcultures, Bodies and Spaces. Bingley, UK: Emerald, 2018. Pdf

See also the continuation of this research in Singapore: ‘Japanese/Korean Popular Culture in Kuwait and Singapore: Resistance and Conservatism’ published in the East Asian Journal of Popular Culture 9:1, 2023.

Bibliography

Mocanu, Delia, Andrea Baronchelli, Nicola Perra, Bruno Gonçalves, Qian Zhang, Alessandro Vespignani. 2013. “The Twitter of Babel: Mapping World Languages through Microblogging Platforms” in PlosOne 18.

Riesman, David. 1950. "Listening to Popular Music" in American Quarterly 2, 359-71.