Thorsten Botz-Bornstein and Noreen Abdullah-Khan

The Veil in Kuwait

Gender, Fashion, Identiy

Palgrave Pivot 2013

The evolution of traditional vestimentary culture in Kuwait from 2011 to 2025

An old study revisited

In April 2011-12 we conducted a survey on Islamic veiling at the Gulf University for Science and Technology (GUST) in Kuwait. The study was published in 2013 as a book. Our book The Veil in Kuwait (2013) explores the complex reasons behind why women veil and how they are perceived by those that do not veil. Religion, culture, family, tradition, and fashion are all examined. Another purpose was to view the veil through the prism of recent international developments that have transformed veiling, at least partially, into a fashion phenomenon. By 2011, international research had shown that in many Muslim and non-Muslim countries the veil was no longer necessarily a traditional item but was influenced by fashion and other contemporary phenomena.

In December 2025, I decided to reproduce the same experiment and to redo the count at the same place and under the same conditions. See the results below.

The result of the 2011/2025 comparison is:

Hijab

2011: 66% wore the hijab, and 34% did not.

2025: 44% wore the hijab, and 56% did not.

Dishdasha for male students

In 2011 we did not count the number of men wearing a dishdasha, but the number seems to have increased. In 2011 the dishdasha was certainly worn by a minority. In 2025 it is worn by 66.8% of the male students.

Abaya

In 2011, 13.5% of the total of female student population wore an abaya.

This went down to 5.6% in 2025.

In 2011, 23% of covered girls wore an abaya.

This went down to 13% in 2025.

I reproduce here these paragraphs from our 2013 book because the topic remains interesting:

2.2. Family Background of Students

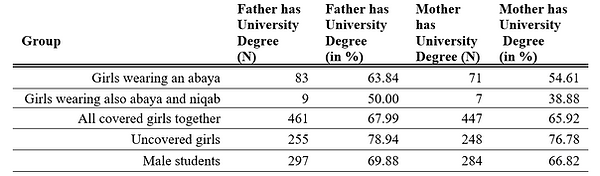

The family background of students is not homogenous in terms of education. 68% of the ‘Covered Girls’’ fathers have university degrees against 79% of the ‘Uncovered Girls.’ The difference is important. In the two independent sample T-test, the two-tailed P-value (indicating statistical significance) falls underneath 0.01 points when calculating the above values, which means that the difference is significant by conventional criteria. In spite of this, we hold that the difference is not important enough to speak of an educational gap between ‘Covered Girls’’ and ‘Uncovered Girls’ parents.

70% of the ‘Male Students’’ fathers have university degrees. Within the ‘Covered Girls’ category, the fathers’ education rate goes down for ‘Abaya Wearing Girls’ (64%) and ‘Niqab Wearing Girls’ (53%). The proportions remain almost the same when it comes to the mother’s education. 66% of the ‘Covered Girls’ mothers have a university degree against 77% of the ‘Uncovered Girls’. Again only 57% of ‘Abaya Wearing Girls’’ and only 40% of the ‘Niqab Wearing Girls’’ mothers have a university education.

Chart 4

Cultural attitudes towards the status of women in society do not seem to vary very much. Around 70% of all groups answer ‘yes’ to the question “Do you believe that men women are equal?” with a slight upward tendency from male to female students. Only 54% of the ‘Covered Girls’ state that their mothers have worn the hijab since their early youth (and did not start, for example, after marriage), which shows that for a large part of these students veiling has started at an earlier age than for their mothers. 82% of the ‘Uncovered Girls’ say that they are open to wearing the hijab in the future and 68% of the males affirm that their future wife should wear the hijab.

Transmission plays a major role in veiling. 97% of the ‘Covered Girls’’ mothers wear the hijab against 67% of the ‘Uncovered Girls.’ The use of the niqab, on the other hand, has decreased from one generation to the next. While only 0.02% (n = 23) of the ‘Covered Girls’ group (n = 814) wear a niqab, 19% of their mothers are wearing it.

Please refer to the book to see in which way GUST is representative of Kuwaiti society.

Conclusion

It can be inferred that the presence of religious dress has decreased in Kuwait because of social transformations. Interestingly, this does not concern the dishdasha for males, an item that is not strongly linked to religion. So, there is, in segments of the population, an increased emphasis on tradition but a diminishing emphasis on religion. Furthermore, the preservation of tradition and identity seems now to be the task of men more than of women, which was different in the past.